Second in a series. The dictionary defines "archetype" as "a perfect example or model of something." The Kansas state motto is "Ad astra per aspera," which means "to the stars through difficulties." This series will focus on native Kansan track and cross-country athletes who are archetypes of that state motto, people and athletes who overcame remarkable difficulties to achieve amazing things. Some will be famous, others not so much, but they will all embody the traits that allowed them to reach the stars through difficulties.

Finish of the 2008 Olympic Trials Men's 800 meters/Photo Credit: Getty Images.

- - -

Much like seeing the tip of an iceberg, sometimes when you see something incredible, something even more incredible behind it is unseen. June 30 this year marks the 10th anniversary of just such an event, the 2008 U.S. Olympic Trials men's 800m final in which Christian Smith, of Rozel, Kansas and Kansas State University, produced one of the most dramatic and thrilling races in Olympic Trials history.

But that was just the visible tip of the iceberg.

The even more incredible unseen story behind that race was that Christian Smith was even still alive to run it.

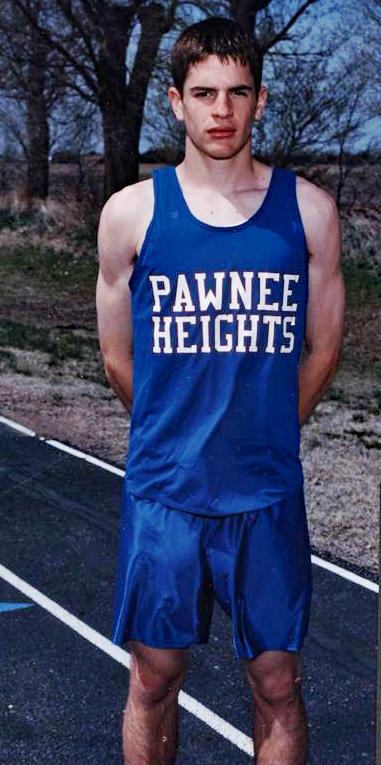

Christian Smith was born 1983 and raised on a farm near Rozel, Kansas (population: 156) in the west-central part of the state. He ran a promising but not spectacular 2:16 for the 800 as an eighth grader before starting high school at Pawnee Heights. From the beginning, Smith's running form was unique and would never resemble the fluid, effortless stride often associated with great middle-distance runners. Thanks more to his farmboy work ethic than his talent, Smith continued to make steady progress by running 2:02 as a freshman and 1:58 as a sophomore (finishing second at the 1A state meet, losing only to his big brother Trevor) before finally breaking out with a 1:53 win at AAU Junior Olympics as a junior. He ended his high school career with a sterling 1:50.6 PR as a senior, one of the fastest high school times in the country in 2002.

Christian Smith of Pawnee Heights High School in 2002.

- - -

From there, it was on to K-State where his intense work ethic and the meticulous training provided by distance coach Mike Smith (no relation) combined to continue his steady improvement. He ran 1:48.1 as freshman before emerging on the national collegiate stage with a 1:46.7 his sophomore year.

After seven straight years of steady improvement, his junior year produced the first, albeit small, hiccup in that steady improvement when he could manage "only" 1:47.

"I was training super hard, and my training was going great, but it just wasn't translating into races like we wanted it to," says Smith. "What I didn't realize at the time was how all that hard training my junior year would pay off so big during my senior year in 2006."

"Pay off big" was an understatement.

Smith rewrote history and exploded onto the world-class scene in 2006, beginning by breaking the NCAA indoor record for 1000 meters, running 2:19.57. He followed that up a month later with his first NCAA national title when he won the mile at the NCAA Indoor Championships in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Fitness often shows up in training before it does in races and, despite those impressive performances, Smith was running workouts that indicated much bigger things might be happening in the near future.

Late that spring, Smith ran a 1200 meter time trial in a jaw-dropping 2:51, which is 3:48 mile pace. He followed that up in a later workout with a blistering 1000 meter time trial in 2:18 (faster than his indoor NCAA record a few months earlier), took a full recovery and then ripped a 400 in 49 seconds. Everything had come together.

After the NCAA meet in June, Smith headed to Europe to test himself against the best runners on the planet. In Lignano, Italy on July 16, Smith proved he belonged in such elite, world-class company when he ran 1:44.86 for the 800, nearly a two-second improvement from where is PR was just a year earlier. If there was any doubt remaining about his new world-class status, Smith removed it nine days later in Sweden by running 3:38.78 for 1500 meters, the equivalent of a 3:56 mile.

He was the only American to run sub-1:45 for 800 and sub-3:39 for 1500 in 2006.

Kansas State's Christian Smith competing against future Olympic silver medalist Leo Manzano of Texas University at the Big 12 Championships/Photo Credit: Kansas State University

- - -

Smith was an "overnight sensation" after nine straight years of grueling hard work. After returning to the United States, he signed a professional contract with Nike and seemed on course to become one of the next great American middle distance runners.

But remember, this series is about people who exemplify "to the stars with difficulty" so if you're wondering where the "difficulty" part comes in aside from the training, just wait, I'm almost there.

Although out of eligibility, Smith returned to K-State to complete coursework for his degree in accounting. In January 2007, he traveled to Eugene, Oregon to train for a few days with the Oregon Track Club (OTC), a Nike-sponsored training group he was considering joining. At the time, the OTC was coached by the legendary middle distance coach Frank "Gags" Gagliano. One of the OTC members was a promising but little-known 800 runner named Nick Symmonds from NCAA Division III Willamette University in Salem, Oregon. Symmonds would go on to become one of the most decorated American 800-meter runners ever, including being the silver medalist at the 2013 World Championships in Moscow, making two U.S. Olympic teams and winning multiple national championships.

While in Eugene, Smith and Symmonds ran a workout with other members of the OTC. "Nick and I just crushed the workout together. We left the other guys behind. It was a blast," recalls Smith about the visit.

Smith returned home in mid-January not knowing that he was entering a fight for his life that would last for months.

While 2006 had been a dream, 2007 was about to become a nightmare.

Smith returned to Manhattan, Kansas from Oregon on a Sunday and the next day had an upset stomach. "I really didn't think too much about it at the time," says Smith. "I just felt a little queasy."

That night, Smith awoke with a stabbing pain in his abdomen. He contacted his girlfriend at the time to take him to the emergency room in the middle of the night.

It was at this point that the nine years of training that had transformed Smith from a 2:16 800 runner as an 8th-grader into one of the best middle-distance runners on the planet would actually play a negative role in his health. You see, runners in general tend to have a higher pain tolerance than most people and world-class runners, well, they have a pain tolerance most mere mortals can't fathom.

Why is that important?

It's important because when the ER doctor (also a mere mortal unfamiliar with the ways of world-class middle distance runners) asked Smith to rate the pain on a scale of 1-10 with ten being "the worst pain imaginable," Smith replied, "probably about a six."

The reality was that, for the average human, the pain Smith was experiencing was more like 9 or 10 on that 1-10 scale. Maybe even 11.

Here's a riddle for you. Do you know what causes abdominal pain that has a pain level of 9 or 10 and does not ever have a pain level of "probably about a 6?"

A burst appendix.

Not inflamed.

Burst, as in ruptured.

So when Smith told the doctor that the pain was "about a six" on a scale of 1 to 10 and that the pain was spread throughout his abdomen rather than isolated to the area of the appendix (because it had already burst), the ER doc pretty much ruled out appendicitis because nobody in their right mind would think that a burst appendix had a pain level of only six.

Nobody, that is, except a world-class middle-distance runner for whom pain was a familiar, frequent companion.

Smith stayed in the hospital two days before being sent home with his undetected burst appendix. His ordeal had barely begun.

The following weekend was a three-day weekend, which he spent with his girlfriend's family in Topeka. All Smith could do was lay on the couch, which led his girlfriend's father to tell him, "You're either really sick and need to go back to the doctor, or you just need to buck up." So, Smith chose to "buck up" by going shopping with his girlfriend even though he could barely stand.

Upon returning to Manhattan, now a week after initially going to the ER in the middle of the night, Smith went to the K-State team doctor who sent him for a CT scan.

The CT scan revealed that Smith had an abscess in his abdomen the size of a cantaloupe.

Smith was readmitted to the hospital, but the infection was too severe to operate so the abscess could only be drained. It refilled, requiring full surgery, flushing the abscess with antibiotics and installing a drain.

Also at this time, Smith was struggling to breathe. That's because two liters of fluid had to be drained from his lungs.

To understand what that's like, picture a two-liter bottle of soda.

Now, pour the entire thing into your lungs.

That was Christian Smith's lungs.

The same lungs that just six months earlier had propelled him to a 1:44 800 in Italy and a 3:38 1500 in Sweden.

Smith remained hospitalized for two more weeks before doctors removed the drain and sent him home once more.

The abscess refilled yet again, so it was back to the hospital for another week, this time in Kansas City. A new drain was installed, as well as a PICC line for antibiotics.

After his discharge from that hospital stay, Smith returned to K-State to finish up his remaining classes. Because of the illness he was forced to drop all classes but one. He attended that one class wearing sweatpants with the abdominal drain tucked discreetly in the pocket. When he wasn't in class, he was in bed.

Doctors were unable to perform the surgery to correct the burst appendix until April due to the infection and the scar tissue that had also formed, blocking his intestine. During the four months from January to April, Smith would undergo a total of 12 CT scans, three surgeries and countless other procedures before the ordeal finally ended.

He had not eaten solid food for four months.

When Smith ran his world-class times the previous summer, his racing weight was 165 pounds. By the time the burst appendix and intestinal blockage were removed, he had lost over 20 pounds of muscle mass.

Once he was finally able to even think about running again, in early May of 2007, he pulled on the spandex half-tights in which he used to run. They were as baggy on him as gym shorts due to the extreme loss of muscle mass in his legs.

He not only hadn't trained for nearly five months by this point, but he had also been bedridden for much of that time. At first, he could only manage alternating jogging and walking for twenty minutes.

That fall, Smith followed through on his planned move to Oregon to train with the OTC and Gags, leaving behind coach Mike Smith who had guided him throughout his college career. He continued to recover and return to training slowly but was still a shell of his former self from just a year earlier.

In early 2008, Smith was selected to run the 1600 leg for the "U.S. Versus the World" distance medley relay at the prestigious Penn Relays in April. Smith got the baton with the U.S. team in first by a large margin. He promptly faded to fourth, running nearly 4:07 for his leg, a time almost 11 seconds slower the mile equivalent for his 3:39 1500 in 2006. That may not seem like much but at the world-class level, where winning and losing is separated by hundredths of a second, 11 seconds is an eternity.

Running message boards lit up with posts from armchair commentators calling Smith a "one hit wonder" and worse.

The Olympic Trials were only two months away, and Smith had a big problem.

To qualify for the Olympic Trials, you must run a qualifying time within a specified window of time that usually begins the year before. Because of his illness in 2007, Smith had yet to run a Trials qualifier and time was quickly running out.

The Olympic Trials 800 field was limited to 30 entries. Smith had to nail a time in the top 30 in the country to get in, and he was nowhere close. It wasn't time to panic, but it was definitely time to change something.

Smith returned to Oregon and had a heart-to-heart talk with Gags.

"Coach Gags is one of the greatest middle-distance coaches in the country, no doubt about it," says Smith. "His record speaks for itself. But he and Coach Smith have very different approaches to training. With the Trials only two months away, I felt like I needed to return to what was familiar. It wasn't that I thought Coach Gags was doing anything wrong, it was just a realization that with everything I had been through I needed the reassurance of something familiar that I knew had produced great results for me before."

Gags agreed that Coach Smith would write the training with Gags overseeing and administering the workouts in Oregon. It would prove to be a turning point, although not a very dramatic one at first. Smith started chasing a qualifying time.

"I was winning races, but they were all in 1:47," says Smith. "I felt like things were starting to click and I was winning some races, but I just couldn't get under 1:47."

Just like the stellar workouts foreshadowing his great performances in 2006 before his fitness showed up in races, Smith's workouts were beginning to show that he was right on the cusp of an improbable breakthrough. In May, Smith ran a workout that would have been unthinkable a year earlier. It was 3 x 400 meters with a full recovery. Coach Smith wanted him to hit all three in 50 seconds flat.

Smith ran an eye-popping 50.4, 48.0, and 47.9.

"But training isn't the same as racing," says Smith. "With all of the time I missed, I just needed to race. I was starting to feel like it was there but I just couldn't get to that other gear yet."

The question was, would the fitness starting to show in his workouts begin to show in race results in time for Smith to make it in to the Trials?

The Olympic Trials began on June 26, and the first heat of the 800 was on the first day of the Trials. Smith continued to chase his qualifying time through June, but could never run any faster than 1:47.26.

A week before the start of the Olympic Trials, Smith had the 31st fastest time, just one place out of the 30 man field.

Unless someone scratched, he would be watching the Olympic Trials from the stands.

That scratch happened at the last minute by none other than Alan Webb, the same Alan Webb who in 2007 ran 1:43 for the 800 and broke the American record for the mile. Webb was struggling to find the form he had in 2007 and opted to put all of his eggs in the 1500 basket.

Christian Smith was in the Olympic Trials.

He was the last one to make it in to the 30-man field, but he was in nonetheless.

The top three make the Olympic team, which meant that Smith had to somehow survive and advance through two rounds to get to the final and climb over 27 runners with faster qualifying times to punch his ticket to the Beijing Olympics.

Previews and predictions for the Trials men's 800 didn't even mention Smith, and if they did, it was negatively. One of the most popular running sites flatly stated, "We rate him as the least likely to make it."

There were three heats in the first round. A total of 16 of the 30 runners would advance to the two semifinals, composed of the top four from each of the three heats, plus the next four fastest non-qualifiers overall.

Smith automatically qualified to the semifinal by finishing second in his heat with a time of 1:47.97. He advanced, but he was still stuck in the 1:47 rut. Despite getting the automatic qualifier, the same website that rated him as "the least likely to make it" didn't even mention his name in their coverage of the heats.

On to the semifinals.

Only the top four from each semi would advance to the final and have a shot at making the Olympic team. The field was now down to the 16 fastest 800-meter runners in the U.S., and only half of them would make the final.

In Smith's semifinal, the 1:47 dam finally broke as he grabbed one of the coveted spots in the final by finishing second in a time of 1:46.02.

However, that time represented yet another big problem for Smith.

To make the U.S. Olympic team, Smith had to not only finish in the top three, but he also had to meet the Olympic "A" qualifying standard of 1:46.00. Smith had missed that standard by 2/100 of a second in his semifinal. Not only would he have to finish in the top three in the final, but he would also have to do it in 1:46.00 or faster. If he didn't, the next highest placing runner outside of the top three who had the Olympic "A" standard would take his place.

Everything came down to the final, even getting the Olympic "A" standard.

Knowledgeable, respected coaches and analysts within the sport gave him no chance. Why would they? It took Alan Webb scratching for him even to snag the last spot in the field, which is hardly the auspicious resume of someone favored to make an Olympic team.

But that only makes what happens next the stuff of legends or kitschy Hollywood movies and it's something you have to see for yourself, so you'll just have to watch this race video.

The race was won by Nick Symmonds, the same Nick Symmonds with whom Christian had "crushed" the workout in Oregon immediately before his appendix burst.

The race announcers didn't even mention Smith's name until the race was over.

It didn't matter.

He'd done it.

His dramatic dive at the finish got him to the line third in 1:45.47, just 6/100 of a second before the outstretched hand of Khadevis Robinson to his right.

He was not only in the top three, he had also met the Olympic "A" standard by a half-second.

A year earlier, Smith was lucky to be alive and could barely alternate walking and jogging for 20 minutes in spandex half-tights that hung on him like gym shorts.

Two months earlier, he had blown a comfortable lead by the U.S. distance medley relay team and faded to fourth against an international field on national television. He became the subject of ridicule and derision by armchair track experts.

A week earlier, he wasn't even in the 800 meter field for the Olympic Trials.

None of it mattered.

Christian Smith now had a title he would have the rest of his life: Olympian.

Finish line photo from the 2008 Olympic Trials Men's 800 meter final/Photo: Lynx Timing

- - -

Sitting in a coffee shop in Gardner, Kansas nearly 10 years after race, I pulled up the video and had Smith break the race down for me.

"We had a plan for every possible tactic anyone in that race might use," Smith says. "Going in, I believed that the three favorites were Nick Symmonds, Khadevis Robinson, and Andrew Wheating, with Wheating being the one I had to beat to make the team."

Instead, Wheating would make the team comfortably in second leaving Smith in the middle of a four-way dogfight for the coveted third and final spot along with Duane Solomon, Lopez Lomong, and Khadevis Robinson.

"Duane Solomon got impatient and went wide early, right after the first lap, and when he did I had a clear inside lane," says Smith.

"With 200 meters to go, I knew I was in it, and that's all I needed. All I wanted was a chance, and now I had that chance."

The post-race celebration and euphoria of the crowd were so intense that it delayed the start of the next event for 20 minutes, something almost unheard of in a meet as tightly scheduled and controlled as the Olympic Trials. If ever there were a race or reason to justify that delay, it was this one.

Smith would not advance out of his heat at the Beijing Olympics several months later. He returned home, finished his accounting degree and continued running in Manhattan, Kansas under the guidance of Coach Smith. The following year, he finished 4th in the 800 at the USATF National Championships, missing a spot on the U.S. World Championships team by one place.

Over the next several years, Smith struggled with persistent and ongoing Achilles tendon and calf issues which hampered his training and preventing his return to the form that he showed in 2006. He qualified again for the 2012 Olympic Trials, but this time there would be no Hollywood ending. The years of hampered training had taken their toll and Smith would not advance out of his heat.

It would be his last track race.

In the post-race interview following the 2012 Olympic Trials below, Smith reflected on his career, said he had no regrets, and described the incredible feeling in 2008.

Not once does he mention his near-fatal illness the year before the 2008 Trials.

That's Christian Smith in a nutshell. Gracious, grateful and no excuses. Ever.

Smith is now 34 years old. He and his wife Sara, a veterinarian, reside in Gardner, Kansas. They have one child and one more on the way.

Smith has put his competitive drive and accounting degree to work as a small business owner. He currently owns four Firehouse Sub stores in North Kansas City, Olathe and Lawrence with plans to add more in the future.

As any small business owner can tell you, being the owner means you do whatever is necessary to make the business run smoothly and it's not nearly as glamorous as most people think it is.

While sitting and visiting with Smith in one of his stores recently, I noticed him looking over my shoulder. He excused himself, saying that he had to help someone. I turned around to see some people waiting to use a malfunctioning soda machine. Smith went to work on it while politely apologizing for the inconvenience.

As I watched, I wondered if anyone waiting in that line had any idea who was helping them, what he had been through or what he had done.

I suddenly realized that moment was a microcosm of Smith's athletic career, and maybe of Smith himself as well. Often unknown and overlooked, he was now doing the same things to be successful in business he had done to be successful as an athlete. He showed up for work, did anything and everything necessary to fulfill his potential, was gracious, and made no excuses. He quietly built a resume of athletic accomplishments the same way he was now acquiring businesses, without fanfare and with very few people being aware that the rest of the iceberg even exists.

In an era of narcissistic, self-promoting athletes, this world could use a lot more Christian Smiths.

Christian Smith inside one of his four Firehouse Sub stores.